We descend from people who risked it all to come to America, made a fortune and lost it all

I grew up in a lower-middle class family that likely would have qualified for food stamps, if my parents had dared apply.

My grandparents, Heinrich (Henry) and Pauline Vogrin, probably would have been shocked, had you told them in the 1920s, that their children and grandchildren would struggle financially.

From their marriage in 1910 until the end of the Roaring ‘20s, Henry and Pauline were doing fabulously well.

They were enjoying economic prosperity and living the American Dream after a daring journey that saw them leave their native country in Europe in 1898 as pre-teens traveling with Henry’s mother, settle in the U.S., learn the language and adapt to their new world.

Henry, born July 29, 1886, and Pauline, born June 18, 1887, had come to Kansas City from what was known at the time as Austria (historically, and now, it was Slovenia).

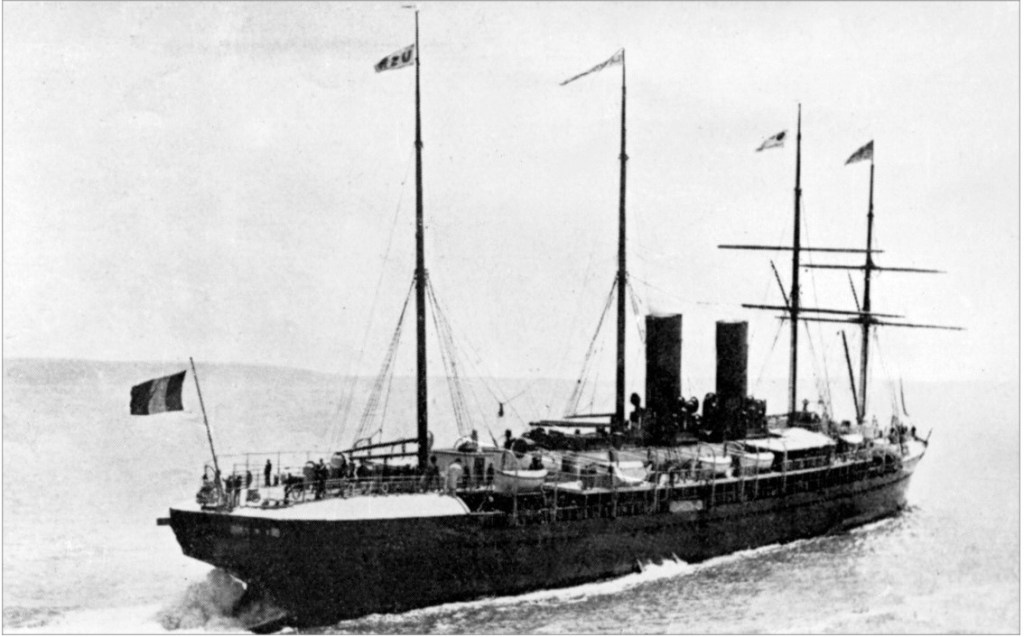

They likely were betrothed, traveling with his 51-year-old twice-widowed mother, Margharetta Loesk Vogrin, on the La Bourgonne, a ship they boarded in Havre, France. It had deposited them May 1, 1898, on Ellis Island.

(The ship became infamous when, just a few weeks later on July 4, it collided with a British ship in dense fog off Newfoundland and sank, killing 549 people. Just 13 percent of its passengers survived.)

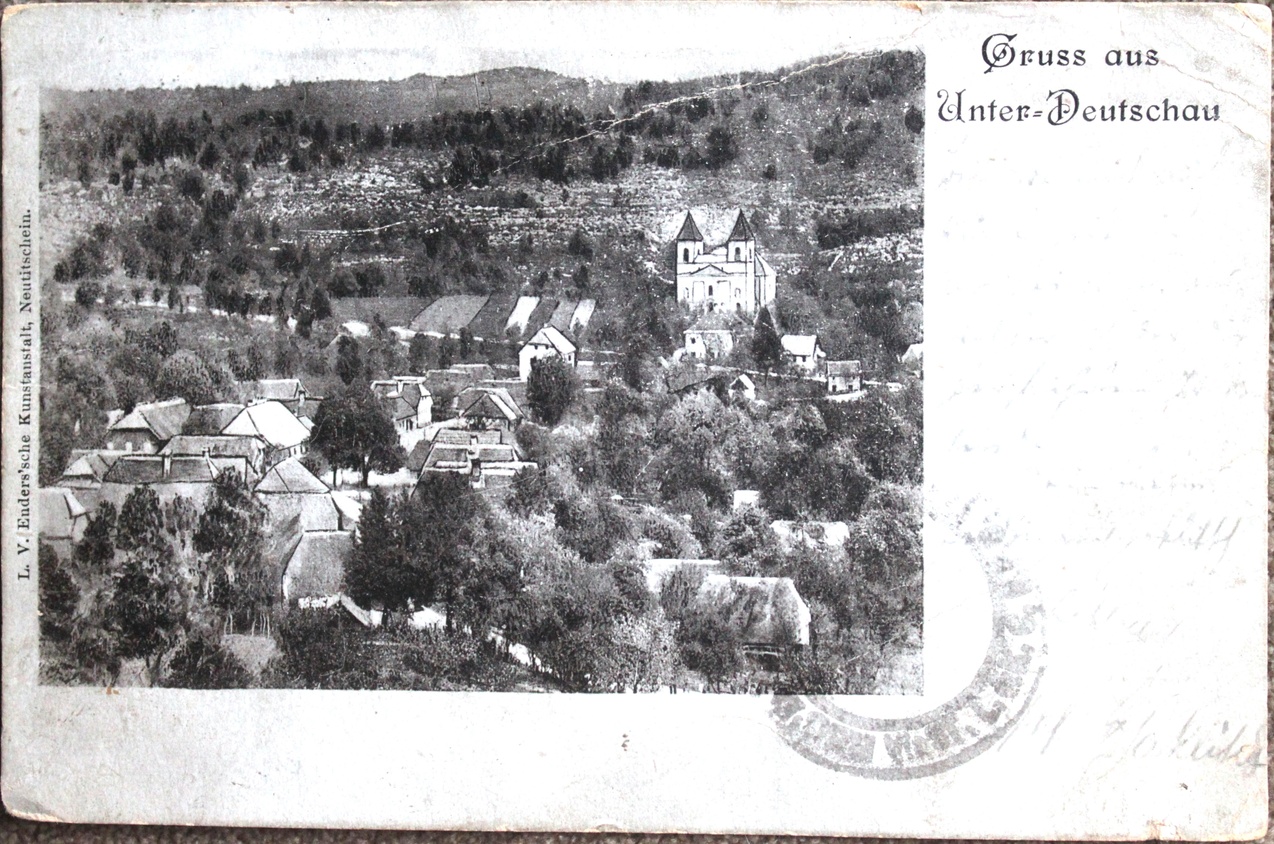

(“Greetings from Lower Germany” — likely Altfriesach in Nesselthal, Gottschee.)

In the 1800s, unrest in Central Europe led many to leave their homes due to religious or ethnic persecution. The Vogrins lived in a German-speaking enclave within what was, and is now, Slovenia in a very unstable part of the region. (Slovenia was absorbed by invading nations and repeatedly wiped off the map.)

Ellis Island documents and other papers showed them coming from of the village of Altfriesach in the parish of Nesselthal in Gottschee, Austria. (Dad always thought we were Germans or “Hunkys” — a U.S. ethnic slur for Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Rusyns, Ukrainians, Slovenes, Serbs, Croatians, etc. )

In KCK, Pauline was reunited with her younger brother Johann (John) Stalzer.

Henry and Pauline married on Aug. 31, 1910. These are their wedding photos.

Why did they end up in Kansas City? Central European refugees like them were guided by the Catholic Church to places like Chicago and Kansas City where massive stockyards and meat-packing plants offered jobs no Americans wanted. (Sound familiar?)

They were terrible, soul-crushing places and the experiences in them left many disillusioned.

In Kansas City, the stockyards and packing plants were located in the river bottoms at the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers on the state border. A Catholic priest in KCK turned his St. Mary’s Church near the stockyards into a settlement shelter for the incoming Catholic refugees.

They endured this because they were so desperate to flee the unrest in Central Europe.

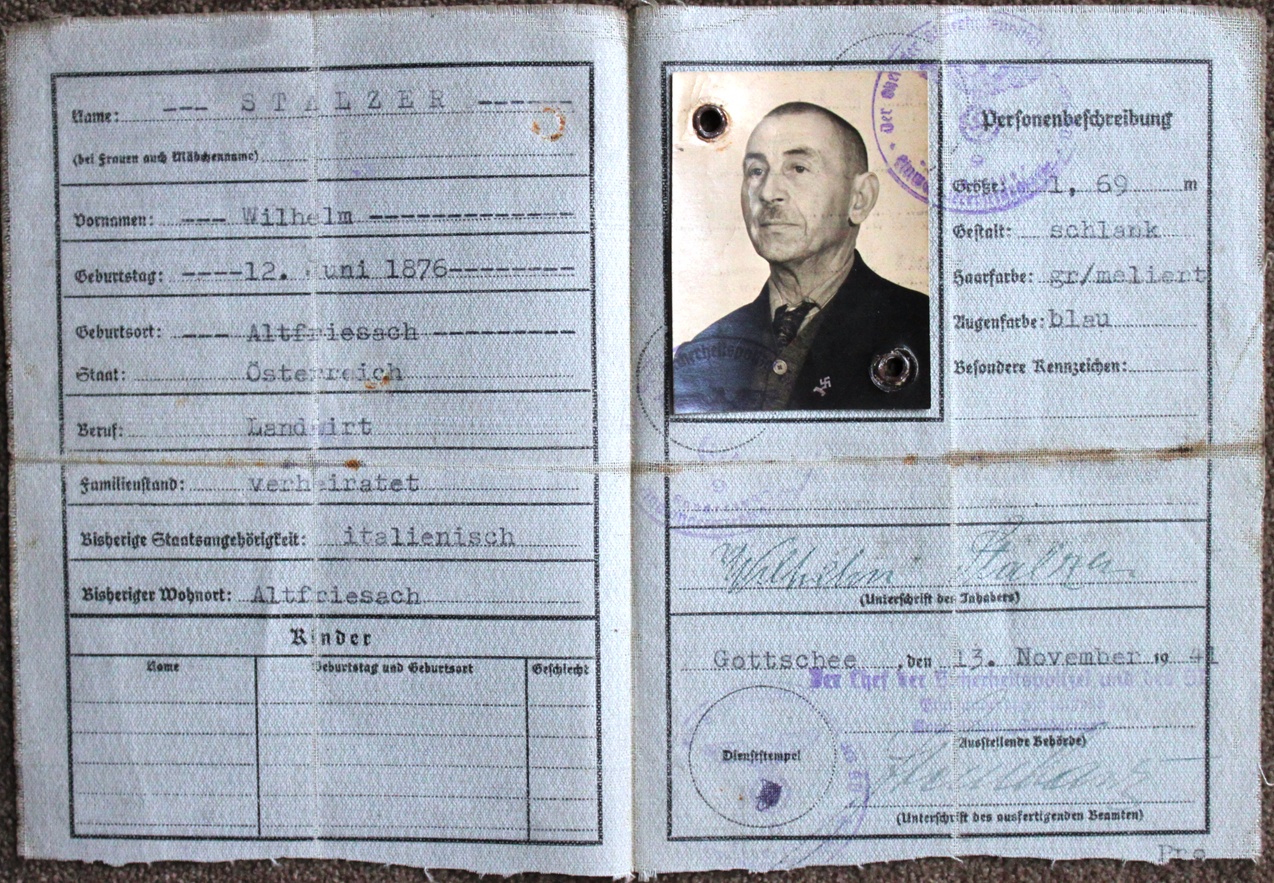

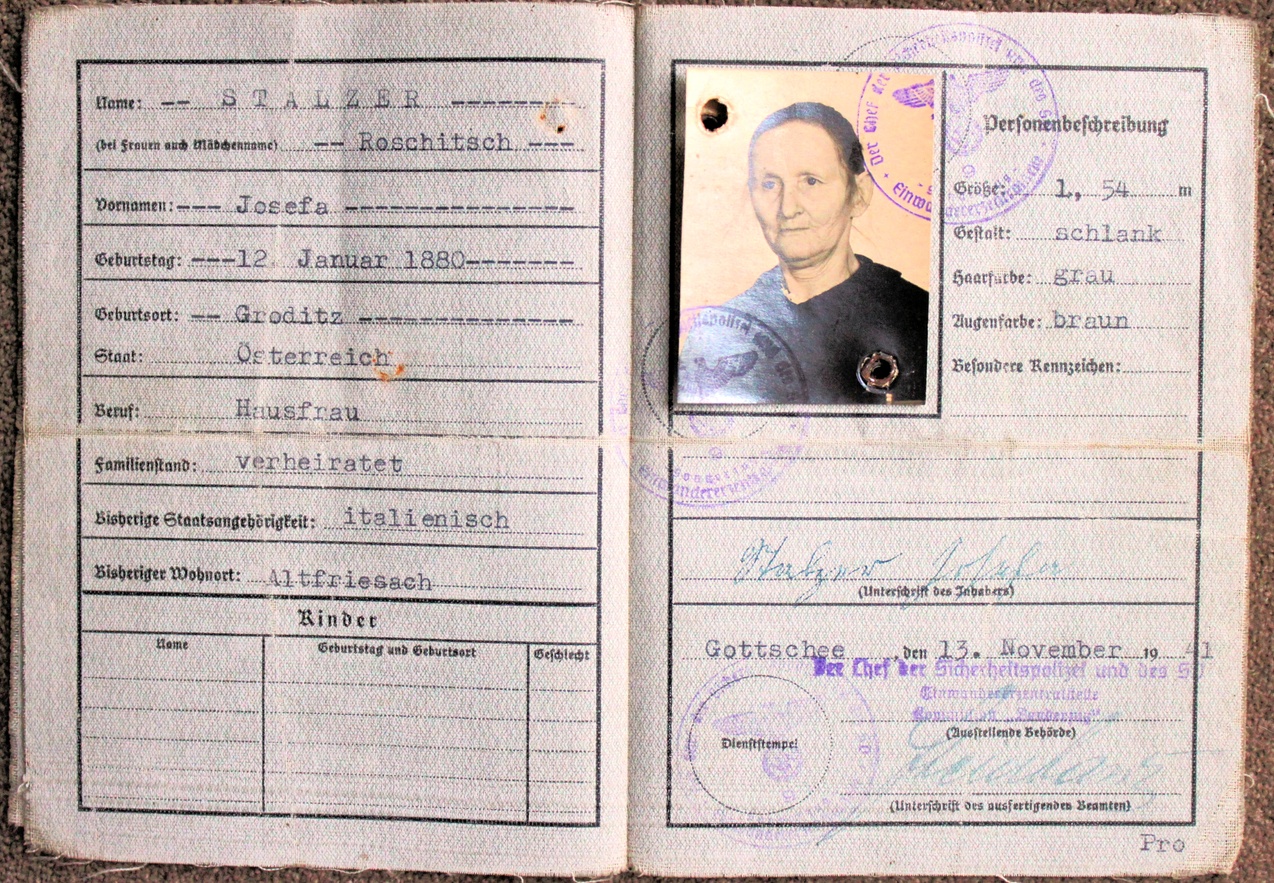

(Pauline’s brother and sister-in-law, Wilhelm and Josefa Stalzer, stayed behind and ultimately lost their homes and were shipped out of Gottschee to a resettlement camp during World War II.

Wilhelm’s letters to Pauline showed him in a German Army uniform with swastikas and he signed them “Heil Hitler!” Ugggh!)

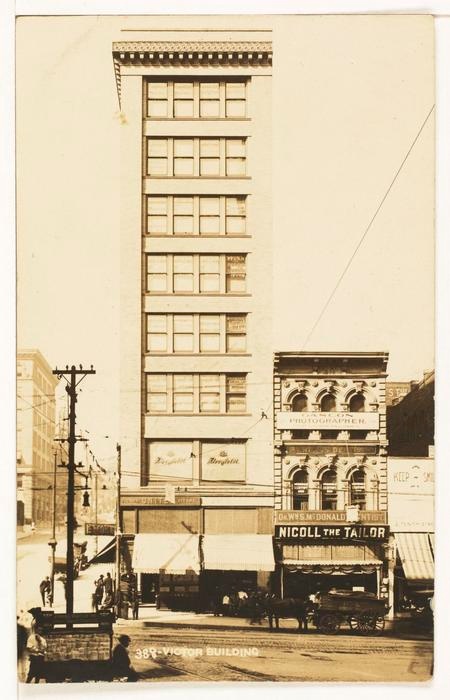

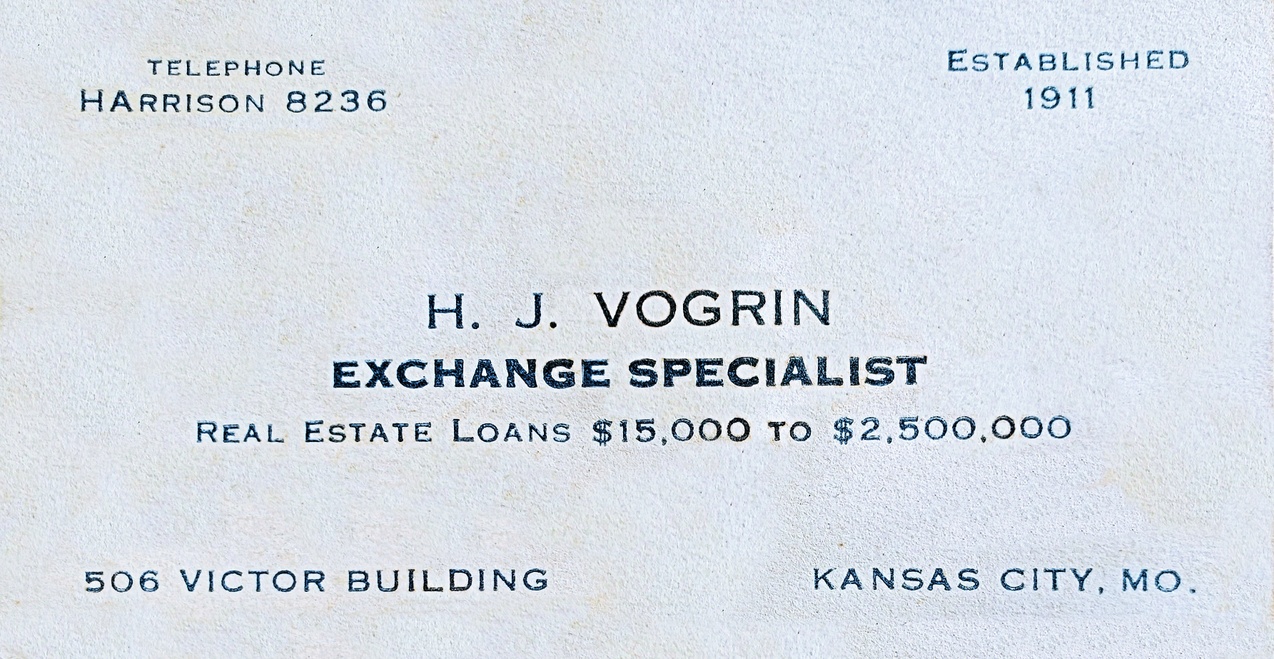

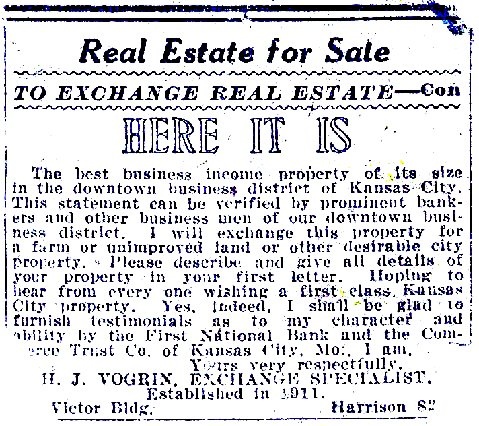

Anyway, Henry and Pauline were lucky. Somehow, he avoided the slaughterhouses and got into real estate. He built a lucrative business and, by 1911, he had an office in the central business district in Kansas City, Mo., in the Victor Building on 5th Street.

There, he advertised real estate sales and exchanges and the ability to make loans via the First National Bank and the Commerce Trust Co. ranging from $15,000 to $2.5 million! That was a massive sum in those days.

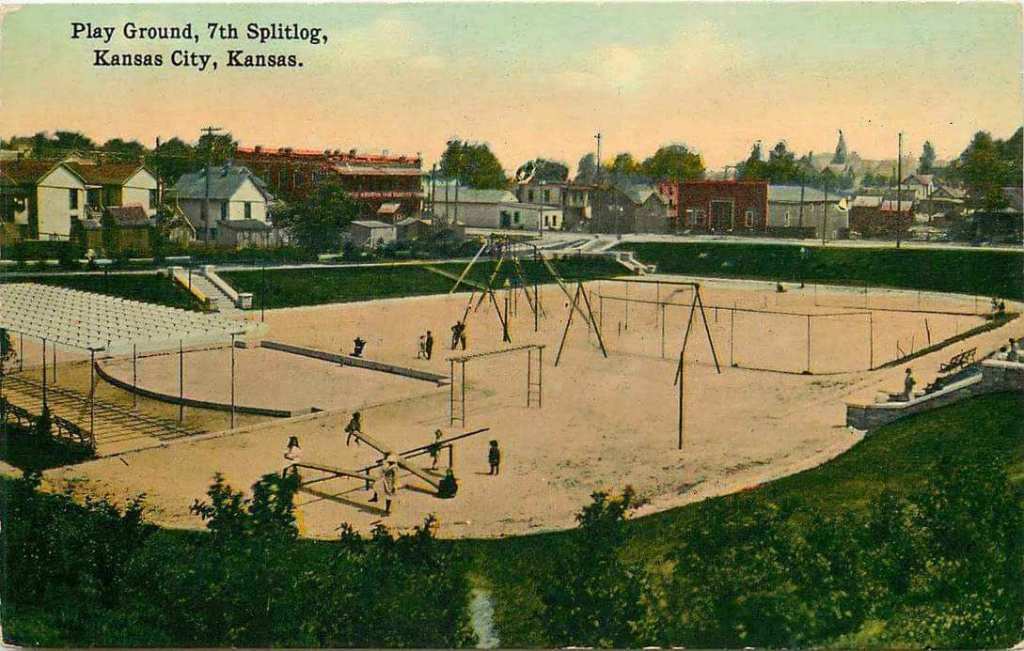

Henry and Pauline bought a home near 7th and Splitlog in KCK where they lived until their deaths in 1963. Both suffered strokes and were hospitalized for months. They died within a few months of each other.

(The Vogrin home, 320 N. Coy, KCK, with the bricks of Splitlog Avenue in foreground.)

(Below is Splitlog Park. The Vogrin home is behind the camera.)

As was the Catholic custom, they donated some of their wealth at the time to help build St. Anthony’s Church where many Slovenes worshiped.

Their donations helped pay for the ornate interior completed in 1924. My Dad’s most prized possession was a gold pocket watch that was given to Henry and inscribed with the thanks of the St. Anthony’s parish.

Besides building the church, they helped build a convent for the nuns of the “Sisters, Servants of Mary, Ministers to the Sick” order. It was built on 18th Street in KCK, next to Ward High.

My Dad and Mom later benefited from Henry and Pauline’s generosity. When Mom and Dad were dying in 1999-2000, the nuns, an order of hospice nurses, cared for my parents every night, 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., until their deaths. It allowed us to keep them at home and avoid a nursing home.)

You might think, given the early financial success of my Grandfather Henry, that my family would have been wealthy.

Sadly, Henry played the stock market. When the stock market crashed in 1929, he became one of the millions who lost everything. And like so many others, he disappeared to look for work, leaving his family destitute.

Grandmother Pauline was left to raise their six children during the depths of the Great Depression. She had no education and spoke little English. Henry wouldn’t come home for years and lived in disgrace until his death.

Luckily, her oldest son, my Uncle Henry, had graduated from the elite Rockhurst High School, a male-only college preparatory school, and Rockhurst College before the crash. He had even gotten a job at the First National Bank of Kansas City, Mo.

Meanwhile, Aunt Molly had earned her diploma at Bishop Ward High School, a Catholic school run by nuns, and gotten the first of a lifetime of secretarial jobs. Together, they supported Grandma Pauline and the four younger kids, including my Dad, until World War II started, essentially ending the Great Depression.

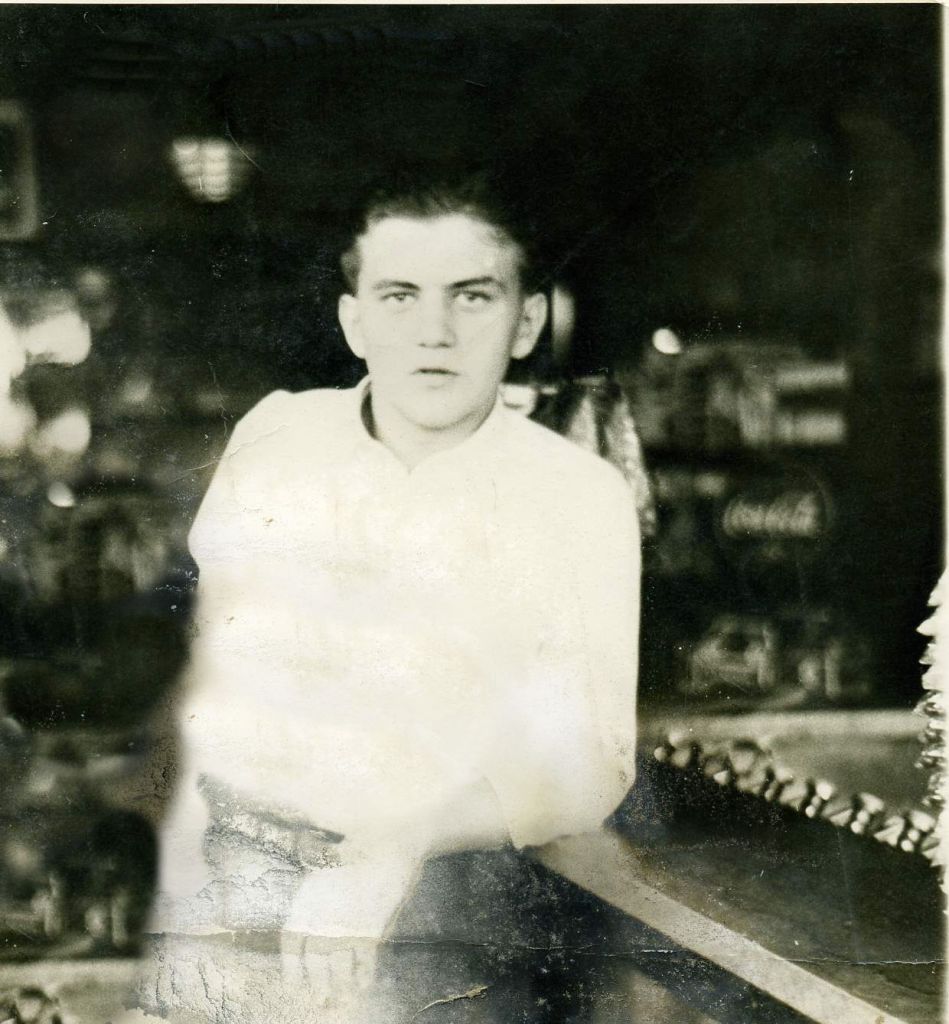

About my Dad: William Joseph “Bill” Vogrin Sr., was a working-class guy, born March 19, 1923, in Kansas City, Kan.

(Bill Vogrin in Coles Drugs Store circa 1940)

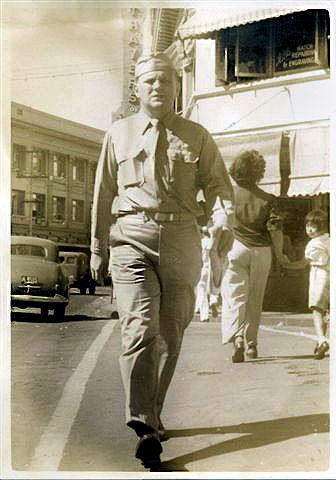

(William Joseph “Bill” Vogrin)

He was a 1941 graduate of Bishop Ward and he joined the U.S. Army in 1942 after the Dec. 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan that thrust us into World War II.

(Dad in Hawaii)

Dad was stationed in Hawaii, climbing to the rank of Technical Sergeant before he was honorably discharged March 7, 1946, after the war, at Fort Logan, Colo.

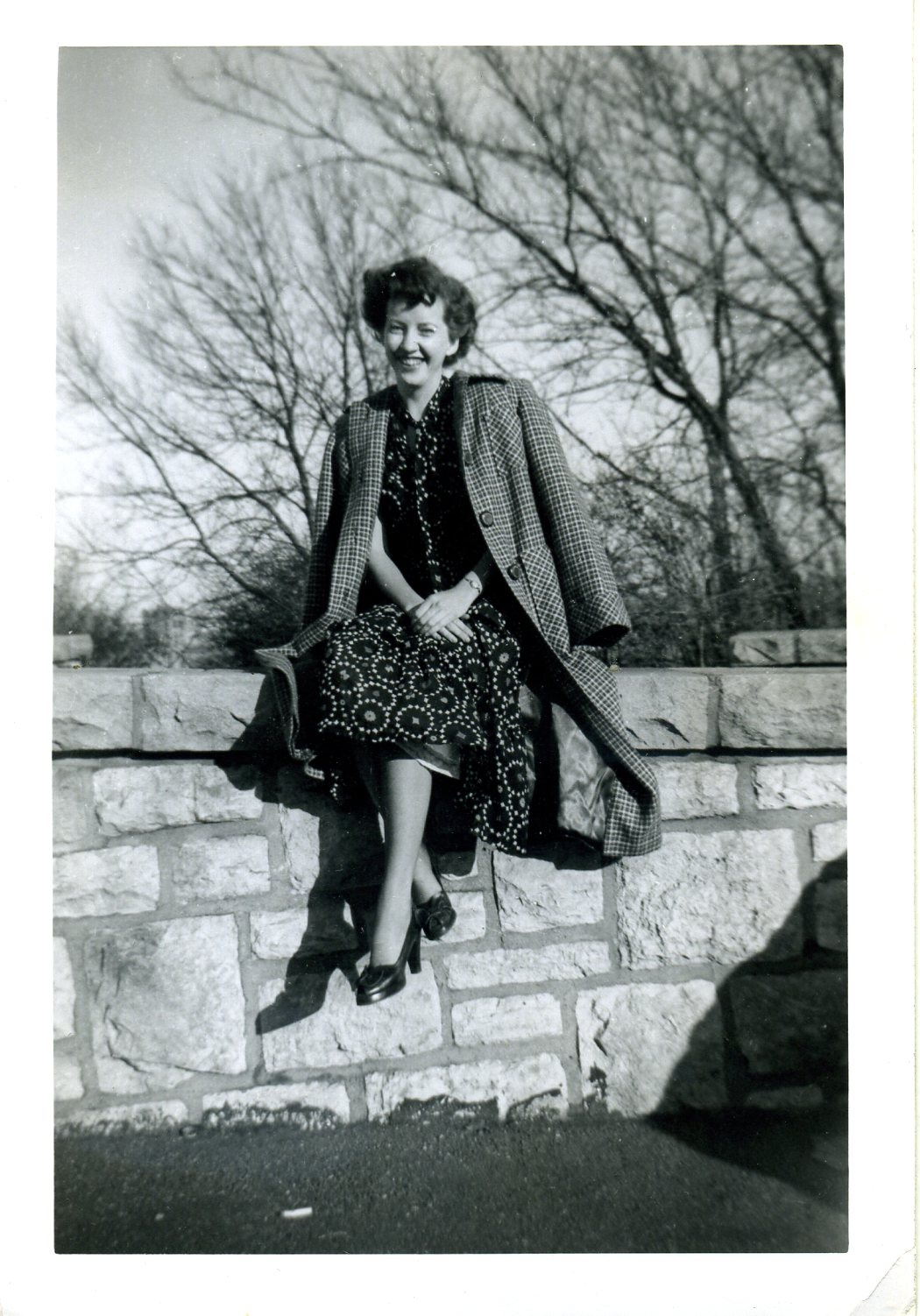

(Elizabeth Ann “Betty” Boland, Northeast High School graduation 1943)

My Mom, Betty Boland, was born into a working-class family, as well, on Jan. 5, 1924, in Kansas City, Mo.

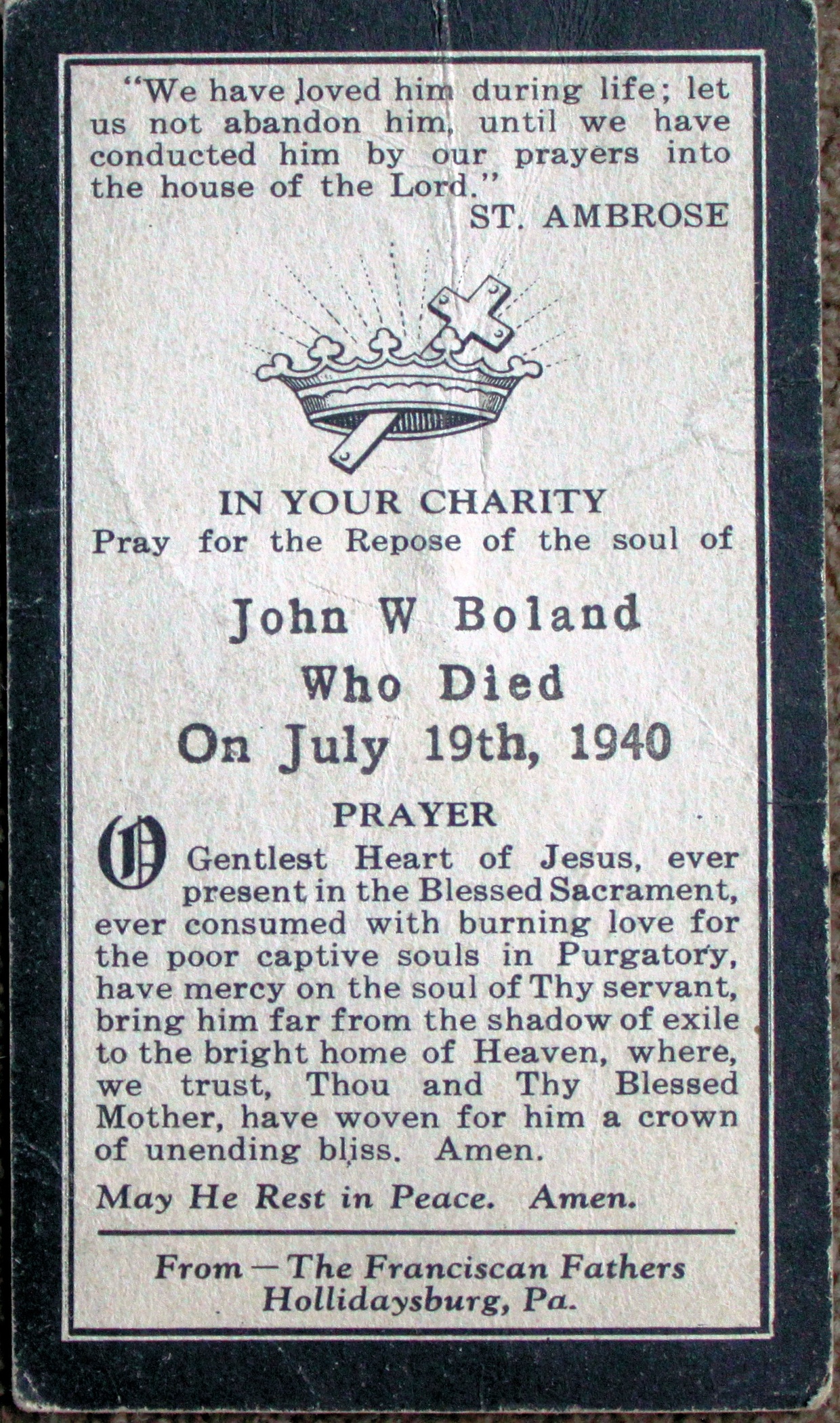

Her Dad, an Irishman named John William Boland, died July 19, 1940, of prostate cancer when Mom was just 16, leaving her mother, Mary Frances Hermann Boland, a single parent with three daughters during the Great Depression. She was German. They lived in a duplex on Van Brunt Ave., in KCMo and Mom graduated from “Dear Old Northeast” High School in 1943. (A classmate was Mort Walker, who later became famous as the comic strip artist who created Beetle Bailey.)

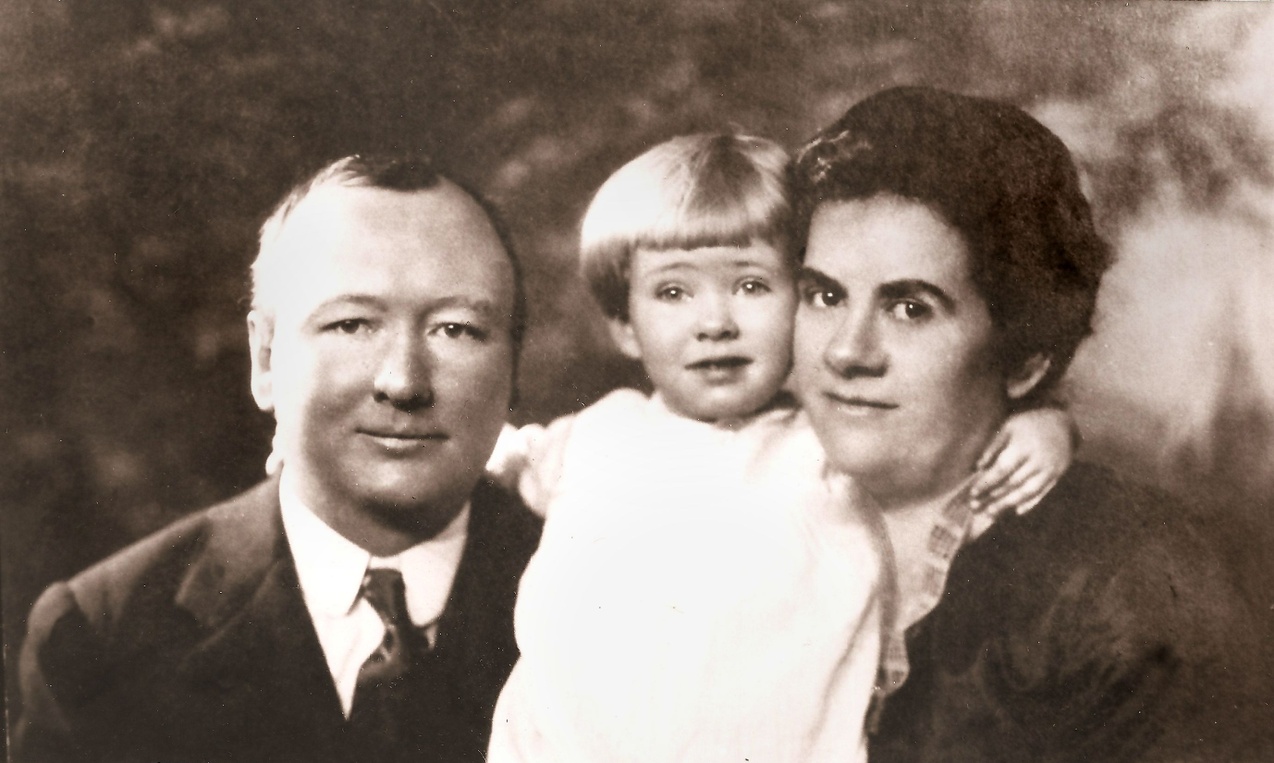

John and Mary Frances Boland and daughter Ruth (My Mom’s oldest sister)

Grandma Boland

Like Dad, Mom served in the war effort. Soon after her high school graduation, Mom went on to work for the American Red Cross. She drove buses, trucks and even ambulances. I recall her often telling Dad to let her drive because she was more skilled behind the wheel than him!

Then Mom went to work on the assembly line at North American Aviation Inc., a factory in Kansas City, Kan., where B-25 bombers were produced. It was a 75-acre facility that opened in 1941 and eventually employed 53,000 workers – many women like my mom.

During this time, Mom began taking flying lessons and progressed to the point she was ready to fly solo. However, she was under 21 and needed parental permission to complete her lessons, fly solo and become a licensed pilot and her mother, Mary, refused to sign, ending her aviation dreams.

Before the war ended in 1945, Mom worked in Iowa, Nebraska and Colorado for the Federal Aviation Administration as a weather observer and radio communicator.

During a visit to our home in Colorado Springs, Mom reminisced of her time in Colorado. She had worked in Pueblo, where she served as an air traffic controller for the FAA.

It was not a pleasant experience for her. She was part of a team that guided pilots in training back to the airport as they learned to navigate their aircraft and deal with dangerous Front Range winds.

She became misty talking about the heartbreak of sitting in a control tower, talking over the airwaves to a scared pilot who had lost sight of the airport or key landmarks like the nearby Arkansas River or was blown off course. It was torture when she lost touch with his voice and later learned he had crashed in the nearby mountains and died.

When that became too much to take, she moved back to Kansas City (but not before hiking to the top of Pikes Peak in Colorado Springs — an accomplishment that made her quite proud).

When Dad returned to KCK, he took a job running a social club in the basement hall at St. Anthony’s Church.

He was just 23 and a bit wild and it makes sense to me that he ran a club. The few stories I heard from my uncles suggest Dad was unsure of his future and running the club was fun. He had slot machines and “pull tabs” and other illegal gambling devices and there was booze and parties and that’s where he met Mom!

His best story about the club was the night he got a call from a friend on the KCK Police Department warning him that the club was going to be raided due to its gambling machines. He and a buddy loaded their machines in a truck, drove them down to the Kansas River and dumped them off the bridge!

(Dad and Mom celebrate New Year’s at the St. Anthony’s Club in 1954.)

Anyway, Dad and Mom met and were married on June 23, 1951, settling in a little rental house on Barnett Avenue not far from the Vogrin family home and St. Anthony’s.

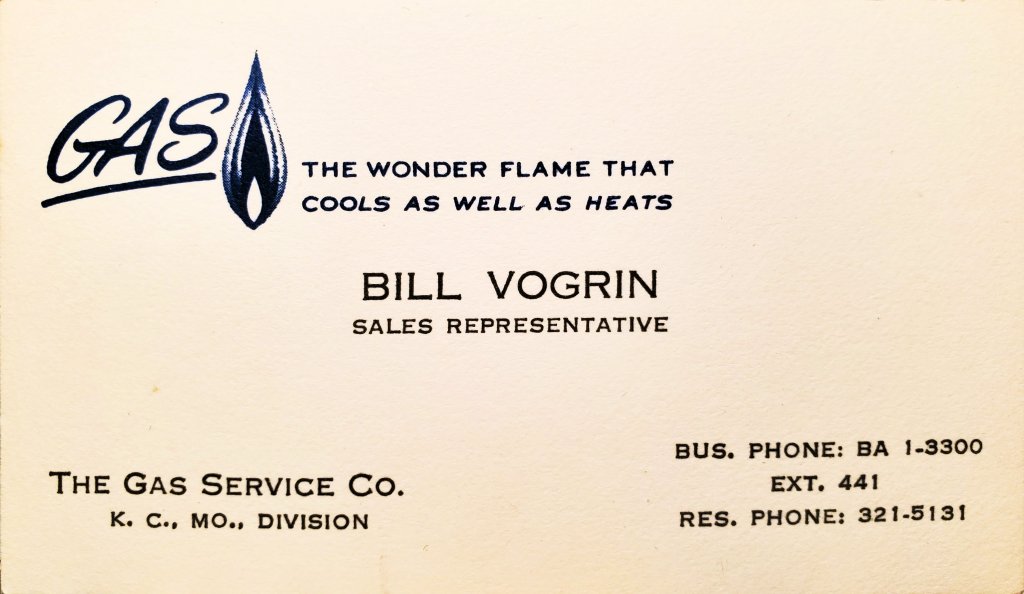

Dad apparently bounced between jobs until Mom became pregnant (for the first of nine pregnancies!) and he took a job with the local utility company, called the Gas Service Co.

Over the years, he did a little of everything — reading meters, digging ditches to install and repair gas lines — but mostly he sold natural gas appliances.

I always liked it when he was reading meters and digging ditches because he’d drive around in a huge truck with all sorts of heavy equipment. My three brothers and I fought to wear his hard hat, goggles and gloves.

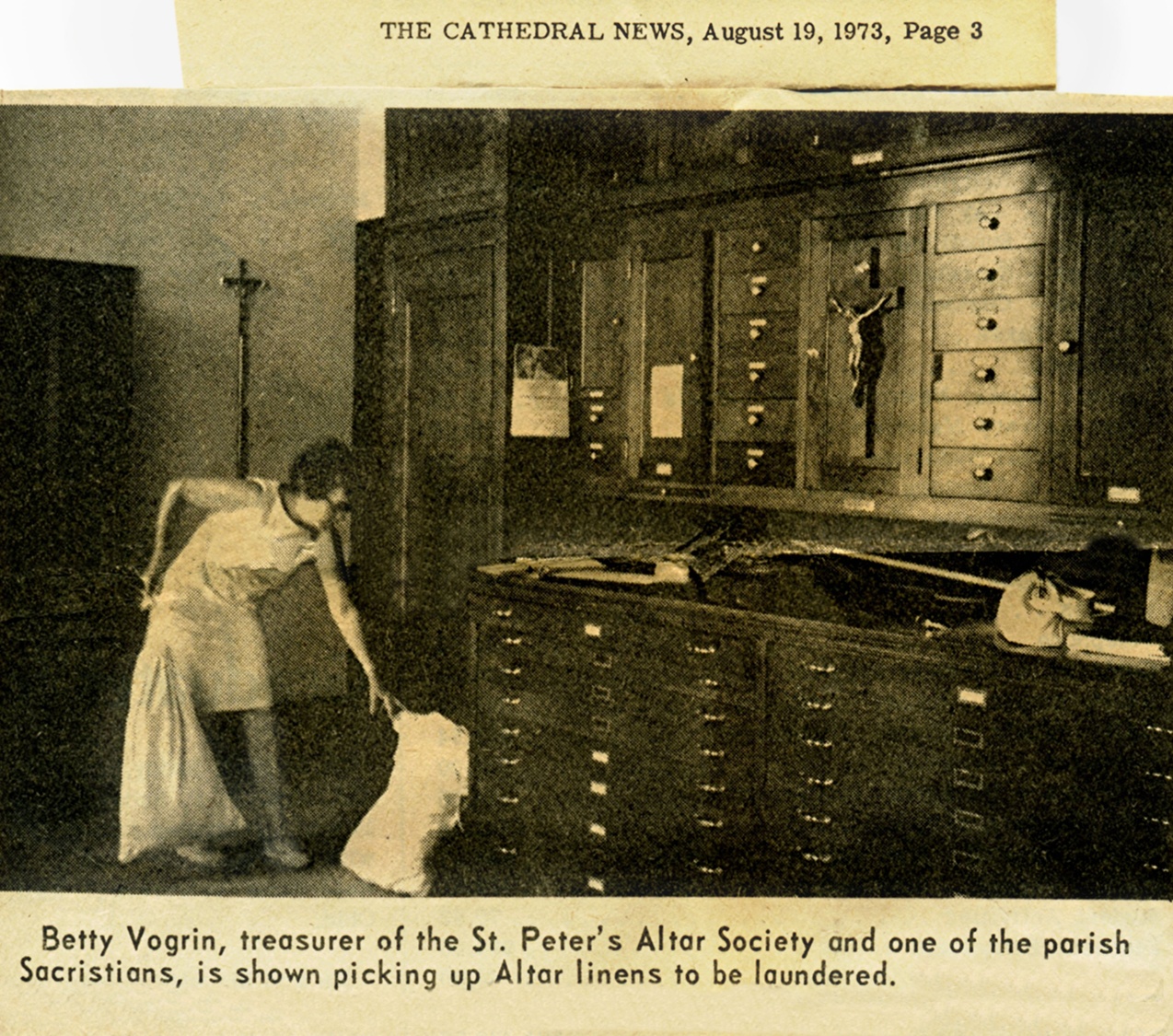

Anyway, the money wasn’t great. My Mom took in laundry to supplement the household income. She did all the laundry for our church, St. Peter’s Cathedral, including all the church altar linens and priests’ vestments.

I remember her sitting for hours every week at a large industrial ironing machine on our back porch. It was steaming hot, even in the winter. There was a lot of stress in the home and it came out in loud fights between my folks.

All four boys worked. We delivered the local Kansas City Kansan newspaper, mowed grass in summers and shoveled snow in winters to earn cash. A buddy Joe Tomelleri and I even took orders for doughnuts on Saturday mornings, went down to a neighborhood bakery, bought them and pulled them home in a wagon, delivering door to door for a small fee.

Meals at our house were pretty predictable. Eggs and cereal for breakfast. Peanut butter and jelly or bologna for lunch. For dinner, lots of hamburger, macaroni and cheese, tuna, chicken and rice, spaghetti and potatoes, apple sauce and milk. We sat crammed around a kitchen table.

Sunday was different. The Sunday noon meal after mass almost always was roast beef, potatoes and vegetables, like carrots. Dad often handled that meal and it was in the oven for a couple hours before we all ate at the dining room table.

And leftovers. We didn’t waste a thing. My mom would throw things together, call it hash and serve it. Or call it mush and fry it. Or bake together strange assortments of ingredients with mystery broths.

If you couldn’t stomach dinner, you went hungry. Period.

If we went out to eat, it was someone’s First Communion, confirmation or graduation. No pizza delivery driver ever rang our doorbell on purpose. And soda was rationed on Saturday night when we splurged on homemade pizza with hot dog toppings. Sunday night was almost always cheeseburgers and chips.

My mother made bread and shopped at “Save On” in the warehouse district down by the Kaw River. She’d bring home expired, dented or damaged food because it saved money. It’s the same reason we all wore hand-me-downs and, for example, when I played soccer as a kid, I stuffed cardboard in my socks rather than fancy, store-bought shin guards.

The Great Depression was long over but my parents never forgot the lessons of saving money. And it’s the reason I’ve tried to teach my own kids to save and be smart with money and appreciate our good fortune.

It’s part of my oft-repeated lecture to my kids about the importance of studying hard, getting good grades so they could go to college, as I did, and make a better life for themselves.

I made more money my first year out of college, working as a reporter for The Associated Press, than my dad made in any year of his working life. I want the same for my kids.

###